.

Lights out, nobody home, in this old photo

The late

David Mumford of WDI was a great source of information for Disney park historians. According to LF reader Mike Cozart, Mumford once told him that a large trove of negatives and slides for use in the parks came to light many years ago when the Disney Studio was clearing out buildings, including full final sets for the Haunted Mansion changing portraits. Cozart thinks that the multiple sets of glass slides currently going up for auction and featured in

Van Eaton's Disneyland catalog likely came from that stash. Makes sense. Wherever they came from, they're forcing us to re-write the history of that part of the attraction.

How so? Well, we've always known that one of the first things Marc Davis worked on after Walt assigned him to the Haunted Mansion project in 1964 was concept art for the changing portraits. Some of them consisted of only two pictures (back and forth), but others had three, four, and even six panels. We have all been under the impression that the longer series were either scrapped entirely or abbreviated to two when the Imagineers recognized that there would not be enough time for guests to watch a sequence of changes longer than a back-and-forth between two images. We all assumed this decision came early in the game rather than late. Boy, were we wrong.

In a number of cases, it was the

opposite of what we thought. Rather than condensing the longer concepts to two images, the two-image concepts were expanded to six. It was only at a later point that some of these were shrunk back down again to two panels and used in the ride. Three- and four-image sets that made the final cut were also padded out to six before slimming down to two for the finished attraction.

Kohn

We know that Ed Kohn (and possibly other artists?) were tasked with translating Davis's concept art to finished paintings, and these in turn were transferred to slides for the projectors, but the fact that Kohn had produced six-panel sets was known to very few, let alone that actual slides of these had been made. We don't know whether Davis produced additional concept art for this development or if the expansion was done entirely at the Kohn stage (perhaps under Marc's supervision).

The complex projectors needed for these morphing portraits were built and ready to go. Glass slides were produced featuring a large number of six-panel changing portraits, far more than were needed. It's possible that the Imagineers had plans to switch them out, keeping the hallway fresh by changing the changing portraits every so often. Whatever the case may be, it seems that the Imagineers came very close to actually using the six-panel concept and did not drop the idea until possibly as late as 1969.

In the

previous post, we discussed the Black Prince and the Flying Dutchman six-panel sets. They show us that the history of each painting must be considered separately. The Prince was created by Marc Davis as a two-image concept. It was expanded somewhat artificially and unconvincingly to six, and then it returned to two before the ride opened. In contrast, the Dutchman

started out as four images and was expanded to six by Davis himself, so the six Kohn paintings were little more than a reproduction of Davis's set. Before the ride opened, of course, it shrunk to two, a mere fragment of Davis's original concept.

(We've updated the previous post since the present post was written, so check it out.)

Now, with the publication of the Van Eaton catalog, more previously unknown artwork has come to light. It looks as though concepts rarely seen or heard of and that we never suspected had gone very far in fact almost made it into the ride. Several Davis concepts featuring two, three, four, and six panels are now represented by Kohn paintings that were transferred to glass slides, although many of these slide sets are incomplete.

It would be interesting to learn exactly when they canceled all that work and reduced the portraits to the simpler, two-picture shows that were there when the ride opened, flickering with the lightning flashes.

For now, let's do the Long-Forgotten thing and look at the new artwork, adding our comments, for what they're worth.

April-December

We've known for a very long time that April-December (removed in 2005) was originally April-June-September-December in Marc's concept art:

This was expanded to six. Kohn images 2, 3, 4, and 5 are seen for the first time in the Van Eaton

catalog (Nov 2015). The first and last slides were the ones used in the ride. (You should know that

here and throughout I've corrected the color, since all of these slides were starting to turn magenta.)

(adapted from digitally-improved images by Bair Pinuev)

Random comments: (1) The second "April" panel is practically identical to the first, but there are small differences in locks of her hair. Apparently the idea was to start off the metamorphoses with very subtle changes. We saw the same thing going on with the Black Prince, where the second panel is very little changed from the first. (2) The first "June" is close to Davis, but the second seems like a completely new character. Fun. (3) The difference between the Davis and Kohn "Septembers" is as great as the difference between their "Decembers." Me, I like them both. (If it had been up to me, however, I would have called the second June "August" and renamed September as "October.")

April is my favorite of all the changing portraits (see

HERE and

HERE).

So yeah, I've been geeking out big time over this one.

(Update: Went for $6250 at auction. Highest for any set and fourth highest

HM item. I'm evidently not the only one carrying a torch for Miss April.)

The Burning Miser

We had a good long look at this guy only a

couple of posts back, and here he is in the limelight once again. He's always been a six-parter, and the Kohn version is a fairly straightforward reproduction, displaying no conceptual differences whatsoever.

(Set went for $4000.)

Actually I'm cheating, since the second panel is missing from the Van Eaton set, but it was easy enough to re-create it. I noticed that the only difference between Davis 1 and Davis 2 is some flames on the man's hands and back, so I just 'shopped Davis's flames onto Kohn 1 and

ta-da, that's what the lost Kohn 2 must have looked like.

In our original Burning Miser post, we were puzzled by a strange alternate version of the sixth panel that had recently

come to our attention. Now we know exactly what it is: a very poor photographic reproduction of Kohn's final image:

The Cat Lady

Davis originally conceived of the Cat Lady as a simple two-parter. This was expanded to a six-parter, and curiously enough, the

pictures actually used in the ride when it shrunk back into a two-parter were not panels one and six but panels one and four.

(Went for $4750)

Daphne

This one is a surprise. Up until a few years ago, "Daphne" was only something I had heard about. Then some Marc Davis concept art come to light (courtesy of the Lonesome Ghost), and I published it

here for the first time. In 2019 it was put on display at Disneyland:

Now we discover that Daphne may have been a serious contender.

I'm surprised, because it's such an obscure subject and so little horrifying by comparison with others. As we pointed out in

the earlier post, it's an adaptation of the

Apollo and Daphne myth, in which Daphne turns into a tree. (Marc took Apollo out of it.)

Of course, a much better choice among Greek myths made it into the Mansion: Medusa. Everybody's favorite Gorgon is not represented in these Van Eaton sets, which may simply mean that the collector in possession of Medusa slides is not selling them or that they are in WDI's possession and archived. We know from the January 1965 "Tencenniel" program that Marc did the Medusa set in 1964 at latest and expected her to appear in the ride. When he did Daphne, we don't know, but evidently she came later as there's no trace of her in published photos or concept artwork.

I have to say that I don't know what Marc was thinking here. Did he want

multiple episodes from Greek mythology in the Haunted Mansion portrait hall? Possible, but I wouldn't have expected that. Or if Daphne was put out there as an alternate choice to Medusa, that too is . . . surprising. Seriously, if the vote is between "beautiful girl turns into a tree" and "beautiful girl turns into a snake-haired monster" for inclusion in a haunted house, do we really need a show of hands? Then there's the question of general public acquaintance with the myths involved. Everyone's heard of Medusa, but

Daphne? In the Van Eaton catalog she's misidentified as "Persephone," which I suppose illustrates as well as anything how obscure this particular myth is!

It's one of those "interpretive dance" things, apparently

As usual, there are two panels almost alike. The difference between panels five and six is only a little birdie in the tree. I suppose

it's there as a bit of whimsy to lighten the mood, but in my humble opinion the whole thing isn't scary enough to require comic relief.

(My arrogant opinion is similar.) Also, I think the final panel in Davis's concept sketch is much more interesting than what they did here.

(Set went for $1900)

The Dustbowl

The "Dustbowl" sketch is remarkable in that it is not a Marc Davis concept. This one came from X Atencio, I am

told. Exactly how many images are in the Atencio concept art, I'm not sure. There are at least four, but there could be

more. Whatever it is, there is not a great deal of difference between the Atencio set and the Kohn set (which went for $2250).

Notice how the crow is skeletonized in the final frame. Once again, a bird has been brought in for some comic relief.

This time the relief is needed. The horrors of the American

Dustbowl in the 1930s were hardly ancient history in the 1960s, and this is a pretty straightforward representation of the event, albeit in allegorical form. I had little difficulty pulling up photographic images that were not far removed from what is depicted in this series.

I'm surprised this one was even suggested. I would have thought that 1969 was still a little early to make light of this historical tragedy. How many park guests back then would have had vivid and personal experience with the Dustbowl? And besides, how "haunted house-y" is this topic anyway?*

But what do I know? They were making goofball comedies about WW2 already in the 1950s (Sgt. Bilko) and Nazi prison camps by the 1960s (Hogan's Heroes), so I suppose I shouldn't be surprised that Dustbowl humor wasn't a problem for the Greatest Generation. I have to keep reminding myself that being hurt and offended had not yet been established as the recommended default setting for practically everybody in society. Maybe the problem with the Greatest Genners is that most of them never went to college and therefore never had the chance to learn about the permanent outrage imperative, the glories of grievance, the wonders of whining. But we're off topic. (And if I haven't offended anybody, please accept my apologies.)

The Wilting Roses

For me, the dying flowers are too obvious and too literal as a symbol of mortality. Yes, flowers die, as do all things beautiful and alive. That's food for thought if you're a poet, perhaps, but it's not scary. Even if you

are a poet, that hoary cliché, "hoary cliché" comes to mind. "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may...." Still, I suppose it gets the job done. There really isn't much to say about this one. I note that it didn't take much imagination to expand Marc's three-panel original to six. That's a little cupid inside a heart on the front of the vase, adding an extra dash of melancholy, as well as the name "Disney" in a Latin motto. Was this painting done in 1966, I wonder?

(Went for $1500)

Walpurgis and Watermelon

The Van Eaton catalog also includes a few orphans among their Mansion slides. There's a single Kohn panel from what was presumably a six-panel Witch of Walpurgis set.

(She went for $1300.)

It's fun to compare and contrast her not only with Marc's original sketch but with the "Sinister 11" portrait

still on display in the Orlando Mansion. They're very different, suggesting that Kohn may have had little

to do with the S11 portraits, even though his "December" was reproduced quite literally as one of them.

One supposes that the goat took a little longer to get here in the six-panel set.

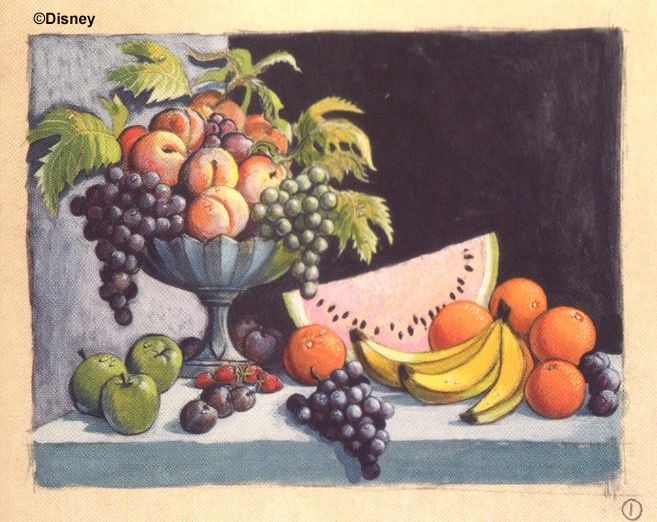

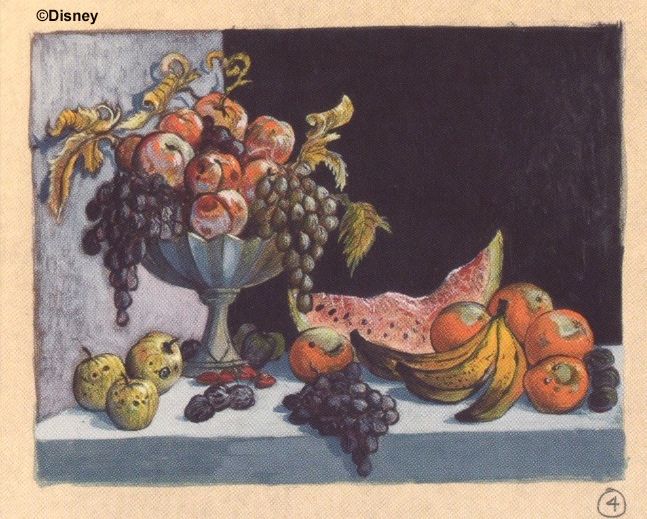

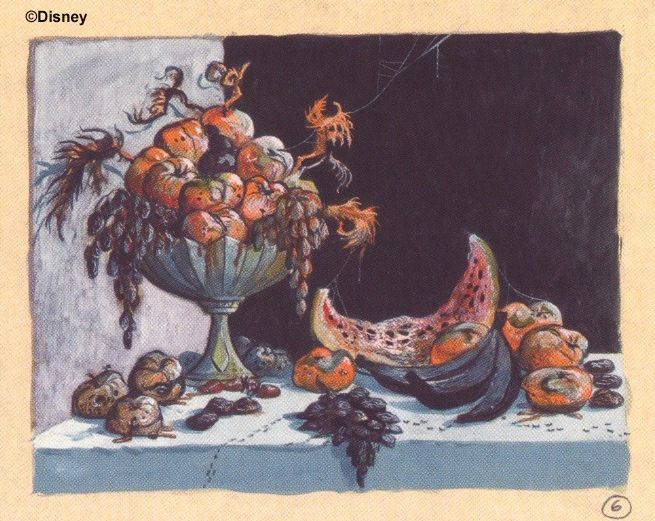

Also in the Van Eaton catalog is a still life with fruit, which you can compare and contrast with what appears to be Marc's original 1964 concept sketch of the same image. What happened in the changing portrait is that the fruit rotted away, much like the roses did. Yawn. Thought provoking, maybe, but hardly the stuff of nightmares. One wonders how this idea beat out some of the other concepts, unless of course practically

all of them were made into slides, in which case there are gobs of delightful artifacts still out there in the hands of collectors or collecting dust in WDI archives, if they're not lost altogether.

It may not be spooky, but it's a pretty good painting in its own right. (It went for $325.)

. . . and it follows Marc's original concept sketch very closely.

In 2019 the full set of Davis concept sketches was published for the first time:

MDIHOW 351

There are a number of other HM relics in the Van Eaton catalog,

but it is these slides that show us something we never knew.

*****************

*I highly recommend the Ken Burns film about the Dustbowl. It's nothing less than amazing how terrible that chapter in American history was.