Updated December 2019

Forgottenistas, what do you think of the cartoons of Charles Addams? Like 'em? Dumb question, I suppose. For me, Gary Larson is a lot funnier when it comes to the absurd and the macabre, and I think Edward Gorey is a better artist and more daring in exploring the blacker sort of humor, but I cheerfully admit that Addams is the trailblazer here, the man who kicked open the doors for all the others.

I don't want to bore you with the same information you can get from any number of other sites. I have other things I want to bore you with. So let's be brief. Addams produced thousands of cartoons for The New Yorker and as illustrations for books and magazines, in a career lasting nearly six decades. He's famous for featuring the macabre and the absurd. Quite a lot of his cartoons involve ordinary-looking people calmly and nonchalantly plotting grisly murders or tidying up afterward. Many involve grotesque and surreal discoveries in everyday environments, like a man noticing that the guy sitting next to him on the subway has three legs.

They're Creepy and They're Kooky

What sets Addams apart from someone like Edward Gorey is the fact that much of his dark humor is laced with plain old silliness. In particular, he gradually created a family of campy horror characters in his cartoons that became the basis of the cult-classic television program, "The Addams Family" (1964-66). The show is a prime example of mid-60's monster chic, a phenomenon which serves as a handy way to classify the Haunted Mansion if you really must situate it within an immediate cultural context. (Other examples of the genre would be "The Munsters," "Milton the Monster," new cereals like Frankenberry and Count Chocula, and all those local "Creature Feature" shows in which a sepulchral host in heavy makeup cracks dreadful jokes and shows rotten old horror movies. And there is gobs of other stuff you would only know about if you grew up during that era.)

If I know anything at all about my readership, I recognize that I am now treading on holy ground.

I've now written a new post dealing exclusively with the television program and its influence on Davis. Read it HERE.

I've now written a new post dealing exclusively with the television program and its influence on Davis. Read it HERE.

Some of you may be surprised to learn that there are only about 150 "family" cartoons in Addams' entire output, and even that number demands a great many debatable inclusions, like ones that feature an Uncle Fester-ish character as a medieval torturer or as a modern insurance salesman. If you are strict in your definitions, there are only a few dozen "family" cartoons. Nevertheless, they are the main reason Addams became famous beyond The New Yorker's readership. By the late sixties, if not earlier, he was truly a cartoonist superstar.

Seeing as how (1) the Haunted Mansion was being developed at just this time, and (2) the fact that "creepy and kooky, mysterious and spooky" became the basic formula for the attraction, it would be surprising if there were no influence from Charles Addams in its development. So is there? Well, yes and no. As we shall see, Addams was indeed a direct inspiration for both Ken Anderson and Marc Davis, and yet there is nothing in the finished Mansion that is incontrovertibly inspired by Addams. That is probably no accident, as we shall also see.

Ken Anderson and Charles Addams

It seems that no one has ever noticed that some of Ken Anderson's concept sketches for the Haunted Mansion were directly inspired by Charles Addams cartoons. I realize that in the absence of written evidence, that's a strong claim, but I think the proof is there.

This important Anderson sketch is the granddaddy of all the HM concept art leading eventually to the Grand Ballroom. It's often reproduced, and many of you have long been familiar with it. We've posted it more than once ourselves:

Anderson had the following 1952 cartoon in front of him when he drew his ballroom sketch in 1957 or 58.

"The little dears! They still believe in Santa Claus."

Besides the general resemblance of the room, note especially the sliding doors, which are practically identical. Perhaps

you're impressed but still hesitant about claiming direct inspiration. In that case, let me call your attention to the chandelier.

Anderson has done little more than reposition a few elements in Addams' sketch. Even the freakin' cobweb is in the same place.

Anderson's organ neatly replaces the fireplace in Addam's sketch, but he didn't necessarily let it go to waste.

We find a fireplace with a shattered mirror overhead in a different Anderson sketch of a similar kind of

room, so it's possible that he appropriated that element of Addams' cartoon for use elsewhere.

We find a fireplace with a shattered mirror overhead in a different Anderson sketch of a similar kind of

room, so it's possible that he appropriated that element of Addams' cartoon for use elsewhere.

By 1954 no less than four anthologies of Addams' cartoons had been published, so there was no problem

accessing even his oldest work. The next example features a cartoon that first appeared in 1939.

First, take a look at this Anderson sketch from the 1957-58 period:

accessing even his oldest work. The next example features a cartoon that first appeared in 1939.

First, take a look at this Anderson sketch from the 1957-58 period:

It's safe to say that Ken had the following cartoon in front of him while he was executing that sketch:

The doors are virtually identical and in the same area in both sketches, and there is even something that looks

like a reflex of the tall, rounded windows in Ken's piece if you look closely. That's impressive, but once again,

is it really safe to claim with absolute certainty that Anderson did his sketch with this cartoon in front of him?

( loving this . . . loving this )

like a reflex of the tall, rounded windows in Ken's piece if you look closely. That's impressive, but once again,

is it really safe to claim with absolute certainty that Anderson did his sketch with this cartoon in front of him?

( loving this . . . loving this )

Mmmm...yeah, it's safe.

Anderson's interest in Addams was not confined to the "family" cartoons, since there are plenty

of macabre visuals elsewhere in the Addams oeuvre. A tip o' the hat goes to GRD for pointing out to

me that another well-known Anderson sketch was probably inspired in part by an Addams cartoon.

First, Ken Anderson:

Next, Charles Addams:

And here's the tell-tale detail that seals the deal.

We're getting used to this by now. You know, it's almost as if Anderson deliberately

left clues in these sketches indicating his source. Fun to think so, anyway.

Here's a sketch more typical of what Addams usually produced for the magazine. There's no trace

of the gothic; it's a completely modern setting. And yet it's still got a usable, macabre gag in it:

of macabre visuals elsewhere in the Addams oeuvre. A tip o' the hat goes to GRD for pointing out to

me that another well-known Anderson sketch was probably inspired in part by an Addams cartoon.

First, Ken Anderson:

Next, Charles Addams:

And here's the tell-tale detail that seals the deal.

We're getting used to this by now. You know, it's almost as if Anderson deliberately

left clues in these sketches indicating his source. Fun to think so, anyway.

Here's a sketch more typical of what Addams usually produced for the magazine. There's no trace

of the gothic; it's a completely modern setting. And yet it's still got a usable, macabre gag in it:

And Anderson (Alt):

If this pairing stood alone, I'd be a lot more cautious in my claims, but in light of what we have now learned, I'm

inclined to mark it down as another direct hit, even without a smoking-gun detail to confirm it beyond all doubt.

So much for Ken "Father of the Haunted Mansion" Anderson. Overall, he seems to have been more interested in borrowing ideas from Addams for the house itself than taking gags and jokes (although see the above). The other great idea man in Mansion history, Marc Davis, did exactly the opposite: he lifted gag ideas from Addams, not architecture.

Marc Davis and Charles Addams

When Alice Davis retells the story about how Walt told Marc what the Haunted Mansion should look like, she usually drops Addams' name. According to her, Marc asked Walt if he wanted a house like the sort of thing you find in Charles Addams, to which Walt replied that he did not. The inside of the place could be as musty and decayed as the Imagineers liked, but he wanted the outside looking nice. Whether or not Alice's recollection is precise on this point, there can be no doubt that Davis did indeed plan to use gag ideas inspired by Charles Addams.

(Incidentally, it seems as usual that Ken Anderson gets short shrift in these discussions. We know that Walt's desire for a pristine Mansion pre-dates Marc's involvement by the simple fact that the house was already built that way before Davis came on board with this project, and we now know that already in the fifties Anderson was visualizing an Addams-like interior for the attraction. Just giving credit where credit is due, folks.)

For our first example, let's take a look at Davis's well-known concept sketch of the ballroom table:

Check out the "table popper," as he's sometimes been tagged. I prefer to call him Kilroy.

New photo! (Aug 2018) Here's the maquette figure:

pic: Duckzz at Micechat

Eventually Kilroy made it into the actual ride, of course.

As usual, the cartoony Davis figures became more realistic humans in the actual ride:

It seems to me this figure may well be inspired by "The Thing," who appeared in about 30 Addams cartoons. He only acquired that name with the TV program, and in the show he was only a hand, but in Addams' cartoons he was an unexplained, funny little man peeping out of nooks and crannies in the sketches, often peering through the balustrade of the upstairs balcony.

The Thing bears at least a passing resemblance to the "table popper" in Davis's sketch:

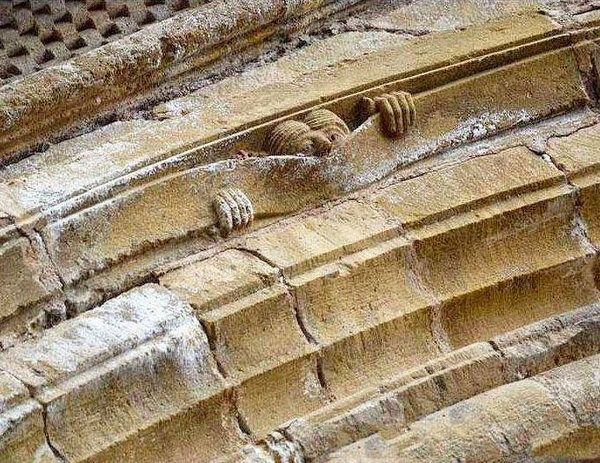

(Apropos of nothing at all, really; be it noted that this type of gag is not new. Here's "the Thing" in an 11th c. Abbey):

Update, August 2016: We have found solid evidence that Kilroy was consciously modeled after the Addams figure. All the AA figures in the HM were assigned "figure" numbers and names, most of these being very generic labels, as can be seen in the sample below, but the table popper is identified as "Small 'Thing'." The quotation marks are conclusive proof, in my opinion, that this figure is indeed identical with Addams' "Thing."

Davis has made him a ghost, but the basic gag is the same. (I call him Kilroy, because in the late 40's

"The Thing" in Addams cartoons resembled the famous "Kilroy was here" graffitum, which was made popular by

American GI's during the second World War and which continued as a pop culture phenomenon throughout the '50s.)

Kilroy as nose art (top) and on the WW2 memorial in Washington DC (bottom)

The idea of "The Thing" as a hand only is believed to be derived from a solitary 1954 Addams cartoon showing human arms sticking out of a phonograph. It's fun to compare this same cartoon with Marc Davis's concept painting of the Brick-Arm Guy, even though we'll probably never know if there's a conscious connection between the two.

In this next example we are again on solid ground. Curiously enough, it represents an Addams gag noticed not only by Marc Davis but also by Chuck Jones over at Warner Brothers, and it ended up in a Bugs Bunny cartoon. It's possible that Davis took the idea from Jones without knowing where it originally came from, and it's even possible that this is all coincidence, but I think it's most likely that Marc was inspired by the same Addams sketch as Chuck.

That cartoon appeared in 1952. Jones' "Broom-Stick Bunny" came out in 1956.

You'll have to look quickly, though, as the bat cage is barely glimpsed in passing.

Marc's sketch we've seen before, but it's always a delight to look at.

Look how much closer Marc's bat is to the Addams originals:

Look how much closer Marc's bat is to the Addams originals:

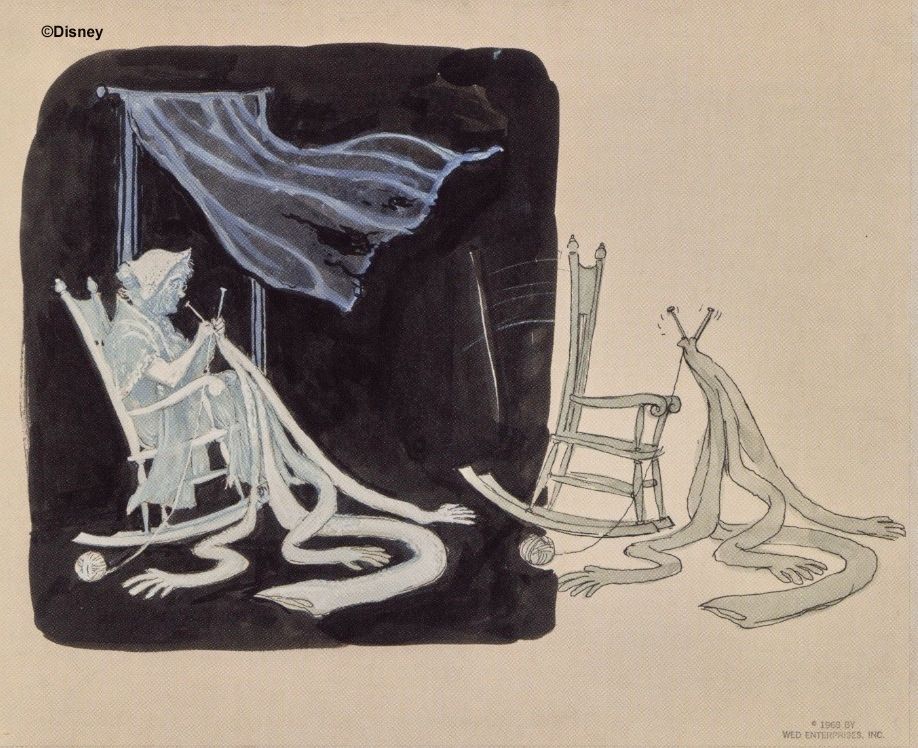

Anything else that looks like a smoking gun; that is, proof that Davis stole ideas directly from Addams? I think yes. Davis drew a concept sketch of a ghostly granny, rocking and knitting a . . . what the hell is that, anyway? Whoever (or whatever) it's for, it has three arms.

Charles Addams, in fact, invented this particular gag.

Addams himself used the sweater gag more than once. In this one, he's got granny doing the knitting, which is how Marc does it.

*cough cough* Excuse me *cough* while I open the window. Too much smoke in here. *cough*

In fact, Davis himself makes explicit reference to Addams in his discussion of the "knitting granny" sketch: "And 'Grannie' sitting at the

banquet table, knitting the sweater with the three arms. A lot of that was very 'Charles Addams' " (The "E" Ticket Magazine 16 [Summer 1993], 23).

In fact, Davis himself makes explicit reference to Addams in his discussion of the "knitting granny" sketch: "And 'Grannie' sitting at the

banquet table, knitting the sweater with the three arms. A lot of that was very 'Charles Addams' " (The "E" Ticket Magazine 16 [Summer 1993], 23).

There is an even more interesting and direct linkage between Marc Davis's crazy

sweater and the "Addams Family" television program. See the discussion HERE.

Like Anderson, Davis did not confine his researches to Addams' "family" cartoons. There is a striking resemblance in tone if not in subject matter between many of Davis's ideas for changing portraits and some of Addams' thought-bubble cartoons in which spouses plot each others' demise. Davis seems to have confined these jokes to homicidal women, while Addams spread the guilt more evenly between the two sexes.

(If you don't get that one, you really need to work on your biblical literacy.)

What strikes me about so many of these Addams cartoons is how easily they could be transformed into two-panel changing portrait gags

of the type Davis produced, or conversely, how easily a Davis concept like the one above could be redone as a thought-bubble cartoon like this:

. Play that Funky Music, White Boys

. Marc Davis, X Atencio, and Claude Coats all did concept sketches of a ghostly chamber quartet or trio.

They're obviously using Ken Anderson's pump organ, as we've noted before, and Anderson in his written plans describes floating musical instruments in the ballroom, so this is another case where Anderson should get credit at least for the basic idea. It's harder to say who first visualized a group of formal, classical musicians, but whoever it was may have been inspired by Charles Addams:

Another hat tip to GRD

. Till Death Us Do Part

. Here's something interesting. Several Addams cartoons feature lethal brides.

( Most readers think that's a branding iron she's holding )

They make you think of Constance, don't they? Especially this one:

Actually, this brings us to the subject of why nothing distinctly Addamsesque made it

into the Mansion, despite his demonstrable influence on the Mansion's two main idea men.

Beware of the Dark Side

It's common enough for discussions of Addams or of Gorey to content themselves with saying things like, "exploring the darker side of human nature" or "black humor" and letting it go at that, as if the simple use of qualifiers like "black" or "dark" had sufficient explanatory power. Unanswered is the question why we think such dreadful stuff is funny at all. I can only give my opinion, for what it's worth.

I think it's because it portrays an ironic distance between the world as we think it is, or more accurately, would like to think it is, and the way it often seems to actually be. Most of us, most of the time, are confident in the basic decency of the random people we come into contact with every day. If you didn't feel that way, you'd never leave your house. After all, there are dozens of opportunities—maybe hundreds—for someone to murder you every day, and it doesn't happen. You don't really expect the guy sitting next to you to be calmly planning your dismemberment any more than you would expect him to have three legs. So Addams shows us that he does indeed have three legs, reminding us how much our belief in a universe that is generally hospitable to good and peace loving people is a matter of faith, not proof. Or take Edward Gorey's most (in)famous work, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, a rhyming abecedarian resembling any number of other childrens' A-B-C books except that it calmly depicts children meeting sudden and often grisly deaths.

How does this manage to be funny? (And of course, not everyone thinks it does.) I think it's because it stands in contrast to the usual childrens' abecedarians, which depict a sunny, harmless world only marginally more true to life than Gorey's gory one. We teach our children to accept by faith the one as the norm and conceal the reality of the other one until they're able to handle it. And so we should, since so far the balance does tip in favor of the bright side. After all, the majority of our kids will manage to survive and will not meet the fate of Gorey's tykes. But we're haunted by the fact that the other is true to life at all, even if it's true less than 50% of the time. Humor is all about irony, the perception of a gap between appearance and reality. Is it not ironic that we must present only part of reality to our children as they grow up if we want them to be mentally and emotionally healthy? If we teach them to be utter realists right from the get-go, they'll end up as whimpering paranoiacs. In fact, it would be cruel not to withhold certain realities from them. Strange, if you think about it. Strange enough to be funny, in a sick sort of way.

As we discussed in Two Taboos, Disney is all about portraying the universe as a place generally hospitable to goodness. In any Disney story, if you're brave and true and keep plugging, things may look bad for awhile but you will come out on top in the end. Always. Walt once said that he himself was not a cynical person and didn't want cynical people working for him. That's much the same thing as what I'm saying here. So the point that Gorey wants to make is a point that Disney will not make, and even when that point is softened by silliness as in Charles Addams, he was still too far out of the light for Disney in the sixties.

In view of all that, it makes sense that those Davis gag ideas for the Mansion that give tacit recognition to the fact that sometimes the Devil wins were precisely the gag ideas that in the end were not used. The closest thing to an exception is the merry and murderous widow in the stretching portrait. Ironically, Walt said it was his favorite! Not ironically, it was the only element in the original Mansion that worked as a gateway for the Constance addition (as the widow is now identified as she).

But it's possible to take even the widow as a deluded fool who will not escape justice in the end, as we have argued elsewhere. You can partner up with Death, dear lady, but only for a time. It's a Faustian deal. He'll come for you too eventually. Maybe that's why Walt didn't read it as being too cynical, too "unDisney"?

But times do change, and a certain degree of recognition that the universe is not quite so consistently stacked in favor of the good guys as we would like to believe has become more and more accepted as appropriate information even for children. Like it or not, we have to take steps to protect them from molesters and abductors, so . . . whispers of Gorey reality will have to be part of their pre-K education. We sacrifice some of their innocence earlier than we used to.

This means that modern kids even at a very young age have been made at least vaguely aware of the dark side. Not surprisingly, this in turn means that even in entertainment venues, little kids routinely see stuff today that would have scared teenagers yesterday and even their parents a few days before that. What passed for "horror" in 1950s films wouldn't cut it as Halloween decorations today.

Cultural changes like this are probably why, for example, some of Tim Burton's edgy stuff is now provisionally admitted to the Magic Kingdom. And that's also why Constance is in the Haunted Mansion, a sour note in an otherwise seamless universe where genuine evil turns out to be an appearance and not a reality.

As a matter of fact, the story of Constance and her husbands seems like exactly the sort of thing Charles Addams might have cooked up, back in the day. So here's an unsettling thought (for some of us, anyway). If kiddie world has caught up with Charles Addams, can The Gashlycrumb Tinies be very far down the road? "Sesame Street has been brought to you today by the letter K . . . ."

Leftovers

I should acknowledge a couple of Addams cartoons that could conceivably be linked with things that are actually in the Mansion, even if it's not possible to claim anything more than that. Some of you will be convinced that there's a link, some not.

In this next one, some may see inspiration for Marc Davis's Corridor of Doors concept sketches. It's possible.

Yet another hat tip to GRD

I have no doubt that other candidates could be found among the thousands of Addams sketches and cartoons.